|

|

|

|||

|

|

|||||

| Maiden Voyage of Mystic Dancer | ||||

|

By: Anne Knorr (Fleming 53-011) Editor: Offshore cruising along any stretch of the Pacific Northwest of the United States is not for the faint hearted. Being the largest of the world's five oceans, encompassing one-third of the earth's surface, the Pacific Ocean reaches the U.S. West Coast after a 6,000-7,000 mile fetch, oftentimes with waves over 18' that have been whipped up by fierce ocean storms. Geologically very young, the coastline of Washington State is rugged, with few (if any) places to duck into if the weather turns sour. For this story, Bill and Anne Knorr made their maiden voyage of the Mystic Dancer on this coastline, exiting the Columbia River to head north the full length of Washington State, then ducking into the Strait of Juan de Fuca for their new (and permanent) home port. Granted, lots of Fleming cruisers from California and Oregon come north along this coastline to cruise in our incredible Inside Passage waters that stretch from Seattle to SE Alaska, but it always amazes me when I hear their offshore passage stories about getting here. When I spoke to Bill and Anne about their trip, I urged them to give us a first-person story of their adventure. In the first part, we'll hear directly from Anne about the cruise; the second part is a Q&A by phone that I had with Bill and Anne after they returned to Colorado following their move of Mystic Dancer to her new moorage at Anacortes, Washington. Ron Ferguson Here's Ann's Story: On Friday, May 17, 2013, my husband (Bill Knorr) and I took the plunge and purchased our first boat, a beautiful 53’ Fleming motoryacht docked in Portland, Oregon. Two days later we were moving Mystic Dancer down the Columbia River towards the ocean and her new home in Anacortes, Washington. In some ways it would be a coming home event since Washington was her original destination from the Fleming factory. Rumors abound about crossing the area known as the Columbia Bar, where the river merges with the Pacific Ocean, a notoriously rough patch of water that has been documented on YouTube videos and warned about by seasoned skippers. With assistance from Captain Mike Cregan, a seaman familiar with the area, we began our voyage down the river late in the afternoon, arriving at Astoria, a moorage close to the bar, well after dark. We entered the ink-black harbor with only the flashing red and green lights marking the channel to guide us safely, and the flicker of lights on the distant shoreline silhouetting the hillside beyond. The river was eerily quiet and still once the sun set, with just an occasional barge transporting goods to keep us company. Monday morning we arose early hoping to time our crossing into the ocean at high tide. Anticipating the worst, we donned our anti-seasick patches and motored towards the mouth of the river. Surprisingly, we were greeted with relatively calm waters, an unexpected but welcomed gift. Maneuvering past crab pots marked with fluorescent orange and white buoys we continued out to sea about twenty miles off shore. Just a faint outline of the mountains could be seen in the distance. Rolling seas made it abundantly clear our sea legs were rusty and out of practice as we lurched to grab a handhold before taking an awkward step. But what can you expect from residents of landlocked Boulder, Colorado? Though we have chartered boats for over 25 years, both in the Pacific Northwest and Caribbean Ocean, open water boating is still a challenge when it comes to maintaining balance. Our second day proved to be the longest as we pressed onward to Victoria Harbor, the provincial capital of British Columbia, at the southern tip of Vancouver Island. Two hundred miles and 24 hours later we slipped Mystic Dancer onto the dock directly across from Victoria’s stately Empress Hotel. Sun rays pierced through cloudy skies and brightly colored flags, red, green, blue, and yellow fluttered in a light breeze. Bells rang announcing the hour with melodic tones that echoed across the bay. Overhead a seaplane banked, then gently glided across the water. Today we would rest and enjoy the sights and food Victoria had to offer us before pushing off to re-enter the U.S. at Friday Harbor for the final leg of our maiden voyage. Anacortes Yacht Charters eagerly awaited Mystic Dancer’s arrival, where she would join the extensive fleet of boats available for charter. On a clear sky day we left Victoria Harbour and motored across Haro Straight to Friday Harbor where we cleared U.S. Customs, then continued on to Fidalgo Bay, our final destination at Anacortes Marina.

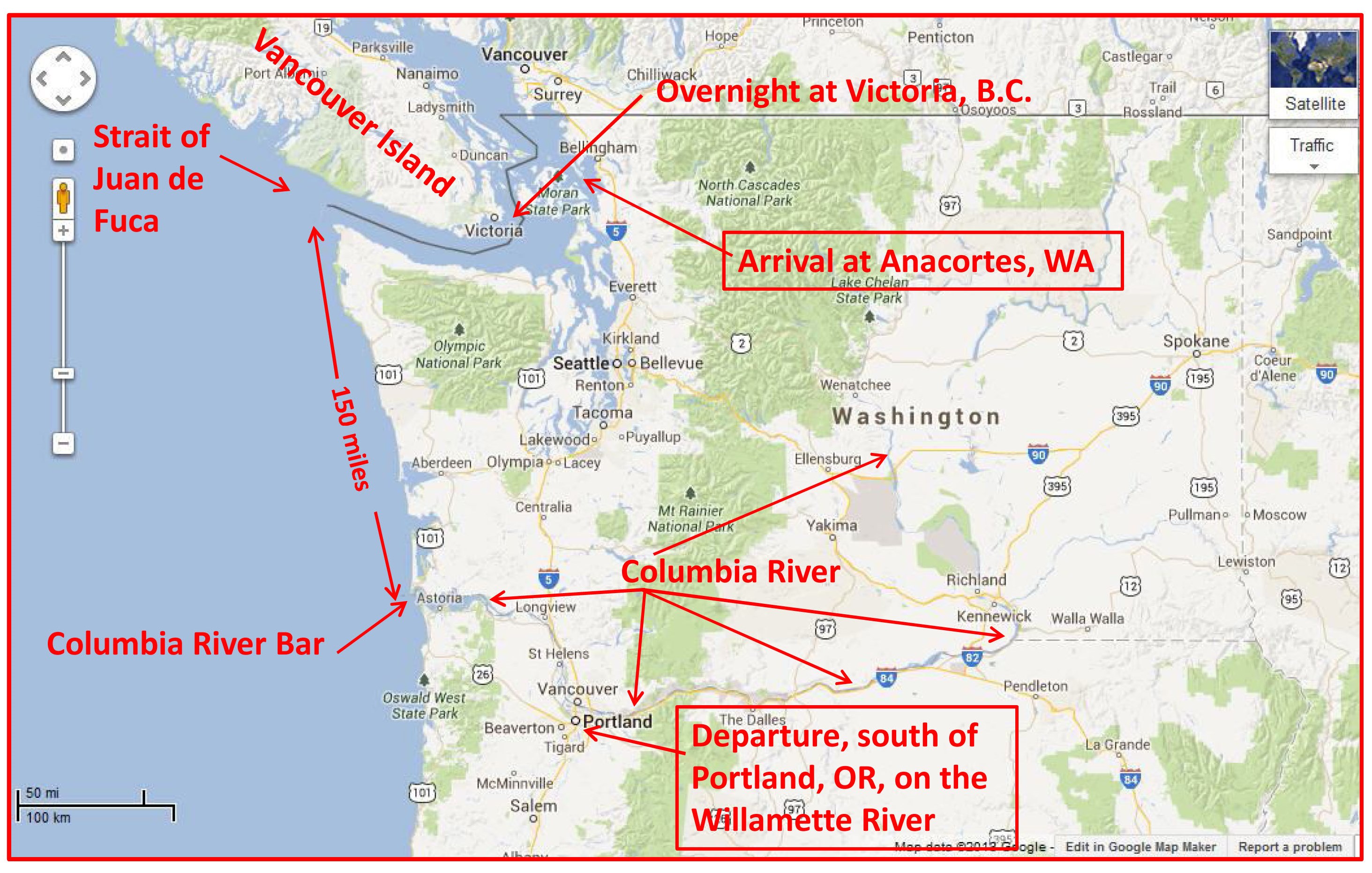

The beauty of the Northwest seaside has beckoned us to explore the San Juan Islands, the Inside Passage, Alaska and other new places we have yet to discover. The Fleming 53 will be the perfect vessel to take us there.  The Washington State coast, from south to north, stretches 150 miles, and while there are two bays one can duck into, once you leave them heading northward, there's nothing bug rugged coast all the way to the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Click on image to enlarge.

The Washington State coast, from south to north, stretches 150 miles, and while there are two bays one can duck into, once you leave them heading northward, there's nothing bug rugged coast all the way to the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Click on image to enlarge.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Question and Answer With Bill and Anne Knorr [RF] Before we begin our interview, a little background on the Mystic Dancer might be of interest. Originally built as Fleming 50, hull #11, she was delivered to the Pacific Northwest in May, 1989, just three years after Tony Fleming began production in 1986. Purchased through Chuck Hovey Yacht Sales in Seattle, she was delivered to Fred and Emily (Pinkie) Stolz, longtime Inside Passage cruisers from Port Angeles, WA. Their first significant cruise on the Fleming 50, named Couverden, was to SE Alaska in 1990, where they met up with their daughter and son-in-law, Andrea and Steve Clark in Ketchikan. After reaching Juneau, they headed west to the tiny island of Couverden, a U.S. Forest Service Marine Park on Lynn Canal and near Glacier Bay, for the yacht’s christening and celebration. In subsequent years, Couverden cruised the Desolation Sound and Broughton Archipelago on the inside of Vancouver Island. In 1994, they contracted with Dunato’s Boat Yard in Lake Union (near downtown Seattle) to lengthen the hull to 53’, giving a much more spacious cockpit area, but more importantly, the extra length lowered the bow to improve visibility. (As a matter of interest, Couverden Island in SE Alaska is the only landmark or place name in North America that the famous explorer, Captain George Vancouver, personally named after himself (someone else named Vancouver Island in his honor). Vancouver's family name before his ancestors emigrated to England from northeast Netherlands was van Couverden - and was subsequently Anglicized to Vancouver. For whatever reason, he chose to name the island after his long-ago family name.) In late 1998, Couverden was sold through Chuck Hovey, and a new Fleming 55 (hull #55-087) was ordered, also taking the name Couverden. The original Couverden was renamed Sand Dollar by her new owner, and the boat remained in the Seattle area for several years. When this owner traded her, this Fleming (technically still 50-011 but effectively 53-011 with her hull lengthening) was sold to a new owner in the Portland area, and renamed to Mystic. This owner cruised Mystic extensively on the Columbia River, as well as northward to Inside Passage areas, before selling her to Bill and Anne Knorr in May, and this venerable Fleming has been renamed to Mystic Dancer. Interestingly, Andrea and Steve Clark, the daughter and son-in-law of the original owners and who still cruise on the new Couverden, lost track years ago of the original Couverden. By sheer coincidence, at Trawler Fest in Anacortes in late May, the new Couverden was temporarily moored in the same slip, awaiting haul-out the next day for new bottom paint, that the original Couverden would arrive at in three days’ time. Bill Knorr, having just closed on the purchase of his new Fleming, happened to be at Trawler Fest that day and dropped by with photos of it. The following is an excerpt from a phone interview with Bill (BK) and Anne (AK) Knorr, the new owners of this beautifully restored Fleming 53, Mystic Dancer. Following their 3-day delivery cruise from Portland to Anacortes, the Mystic Dancer has entered charter service with Anacortes Yacht Charters (www.anacortesyachtcharters.com), where she is available for either bareboat charter or with a licensed captain – very possibly the only Fleming in regular charter service anywhere in the world. As often as they can, Bill and Anne also hope to cruise on Mystic Dancer, and are dreaming of “north to Alaska”, this time making the trip all the way from the Pacific Northwest on their own bottom. [RF] You’ve chartered in Puget Sound and SE Alaska before, but I presume that was all in somewhat protected inside passages and coastal cruising. Was this your first experience at open water cruising? [AK] For Anne, that’s a yes. [BK] I completed a circumnavigation of Vancouver Island in a Valiant 40 sailboat about three years ago. The cruise was part of an off-shore certification course through Cooper Boating in Vancouver (a power and sail charter and school operating from Granville Island in Vancouver, www.cooperboating.com). This was my first and only time cruising through the night before this latest trip with Mystic Dancer. Anne and I have also done a fair amount of sailing in the Caribbean, with some 50 - 70 mile passages in open water, such as St. Lucia to Grenada, but in daylight. And then we chartered a Nordic Tug 37 in SE Alaska, but again, this was in protected coastal waters. With the Nordic Tug, they were pretty picky about my lack of experience with single screw power boats, and while the sailboats we’ve chartered are also single screw, they’ve mostly been catamarans, which are particularly easy to turn. [RF] So, Bill, you felt pretty comfortable with this trip up the Washington Coast, even though it was your first-ever cruise with Mystic Dancer?

[BK] Yes, but we would not have done this passage without a captain aboard. The stories we’ve heard about the Columbia River Bar, and the fact that once you leave Astoria at the mouth of the Columbia River, you really have no options for at least 18 hours. Grays Harbor is a few miles to the north of the Columbia River entrance, but after that there are no other bays to duck into along the coastline until you reach Cape Flattery at the mouth of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Because the boat was heading into charter service with Anacortes Yacht Charters, we hired Mike Cregan, a licensed Captain with AYC, for the trip. [RF] Here’s what Wikipedia has to say about the Columbia River Bar: “The Bar is where the river's current dissipates into the Pacific Ocean, often as large standing waves. The waves are partially caused by the deposition of sediment as the river slows, as well as mixing with ocean waves. The waves, wind, and current are hazardous for vessels of all sizes. The Columbia current varies from 4 to 7 knots westward, and therefore into the predominantly westerly winds and ocean swells, creating significant surface conditions. Unlike other major rivers, the current is focused "like a fire hose" without the benefit of a river delta. Conditions can change from calm to life-threatening in as little as five minutes due to changes of direction of wind and ocean swell. Since 1792, approximately 2,000 large ships have sunk in and around the Columbia Bar, and because of the danger and the numerous shipwrecks the mouth of the Columbia River acquired a reputation worldwide as the Graveyard of Ships.” For a more complete description about this amazing stretch of “the roughest sea conditions in the world”, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Columbia_Bar. [RF] Can you elaborate a bit on your experience with the Columbia River Bar? Anne said it was relatively calm, but I assume there was some noticeable transition from the river’s outflow and the incoming rollers of the Pacific. How far out into the Pacific did you exit from the Bar after the last point of land? Did you get a reading on the wave height and interval within the Bar? [AK] I’m not sure I said it was calm. But from the stories we’d heard, it certainly wasn’t what I expected it to be. It was choppy, but not the huge rollers that you’d expect off-shore. [BK] At the mouth of the Columbia River, the water is very wide, with a fairly narrow channel to navigate through. You obviously have to stay in the channel, in water that’s about 70’ deep, but as you look out at the bar you see the breaking waves – they are off to the left and they’re good-sized waves. When you look at them through binoculars, it’s a pretty good break. Because the channel is so deep, at 70’, the waves don’t break in the channel itself, but the ocean waves meeting with the river current are still there. We have stabilizers, and for the first time for us, because the river had been so flat up to that point, the boat started pitching, and I think we would have gotten pretty sick if we hadn’t taken some seasickness medicine – patches behind our ears. We were hitting the ocean waves bow-on – but they were small enough we weren’t going up one side and down the other – it was more of a shorter chop, shorter wave lengths. You go right by the breaking waves off to your left from the reef, but in the channel you’re in non-breaking water. The previous owner of Mystic Dancer said he’s crossed the Bar several times in the boat, and he’s taken it through with 11’ waves breaking onto the bow, with green water all the way to the Portuguese bridge. He said the good thing is, the boat does really well, going right through it, which is something nice about a Fleming, as it has that high bow. He told us if conditions on our crossing were like that, we’d be OK, but it’s nice to know that the boat’s been through it before and done fine. So that was a sense of comfort. Also, Mike Cregan has gone through the Bar before, so he was familiar with it too. As we crossed through the Bar, we were running at about 10 kts and 2,000 RPM, but we had the river current with us, so the GPS was running a little bit faster. [RF] As an aside, a couple of years ago in the Broughton’s we spoke with a couple from Portland who brought their Defever 50 through the Bar and it took them over four hours to cross it. They left the same marina at Astoria that you overnighted in, and everyone there – including an experienced River Bar Captain – told them it was the best time to go. Because the Bar conditions can change so rapidly, they encountered the Bar at its worst. Part way through the 4-hour vigil, he ended up strapping himself to the helm to be able to hang onto the wheel. He’d bury the nose in a standing wave that he couldn’t push all the way through, and then be pushed back into the trough, where he’d get another run at it. He was afraid if he turned 180° to retreat, he’d broadside so he just stayed with it until they finally punched through. [BK] I’d say it probably took us an hour, maybe an hour and a half, to cross through the Bar. Don’t quote me on this, but I’d guess the overall distance that you have to traverse through the Bar is about 4-6 nautical miles. Somewhere within the Bar, we increased our RPM to 2,200. That got us to 11 kts over the ground, and we were burning 10 gallons an hour. All in all, I thought we really lucked out. We left Astoria at 7AM, and frankly, compared to what we were prepared for, it was just a non-event. But we were prepared for it to be much worse. Before leaving Astoria, we had battened down the hatches, taken stuff off walls, laid everything in the berth and stuffed pillows around it. Nonetheless, it was a very safe feeling. I think that’s the message about crossing the Bar . . . that the previous owner had done it several times previously, and on one trip had taken water up to the Portuguese bridge, surviving in 11’ standing waves, and a passage that took him a while. He also shared a story about another attempt at the Bar when he just turned around and said, I’m not going to do it anymore. But there is a Coast Guard unit there that puts out a pretty good weather report. There’s a lot of weather information that you can receive by just getting on the radio, or you can telephone them. After crossing the Bar, we went 20 miles off shore, primarily to escape the crab pots – and there were a lot of them! – but also to be in deeper water where we got a smoother ride. To miss the crab pots, we were constantly making sharp turns, left and right. Our autopilot has a dodge-right/dodge-left button, and we relied heavily on that. Many of the crab pot buoys were buried in the waves, so you couldn’t see them until the last second. The pots were typically set in patches of four, so if you turned to miss one, you’d likely turn right into another one from the same set. We thought we’d be safe from the pots if we got offshore to 300’ depth, but we weren’t, and it wasn’t until 20 miles off the coast that we got away from them. [RF] Once you were out in the open ocean, what were the waves and swells like? [BK] I’d say they were 6-8’ swells. The seas were running from the southwest, but the wind was blowing mostly on our bow, so the sea conditions were a bit confused. It wasn’t like a nice, gentle roll like you have a lot of times in a sailboat. My offshore experience has only been in a sailboat, and frankly, a sailboat is much more comfortable on open sea conditions like this. A powerboat kinda’ lurches, whereas with a sailboat you have that tension with the sail – almost like a gyro – and it helps the boat push through waves. With the Fleming, it wasn’t uncomfortable, but it also wasn’t like being on the Inside Passage where you’re more protected. The stabilizers helped a lot. Out in the open water, it was mostly a matter of not getting seasick. We both got queasy. [RF] Were stabilizers on the boat when it was first delivered from Fleming? [BK] No, stabilizers, as well as a bow thruster, were added at the time of the aft deck extension. The background on the deck extension is an interesting story. If you recall the luxury tax of the late 1990s – the Stolz’ determined it was less expensive to upgrade the Fleming 50 to a 53, plus add the stabilizers and bow thruster, than to purchase a new Fleming, because you didn’t have to pay the tax. At the time, the tax alone on a new Fleming was more than the upgrade cost. [RF] Throughout the long day and night, how did you handle the crew shifts at the helm? [BK] Unlike the time we did the circumnavigation of Vancouver Island in the sailboat, where we had set watch times – and if you were three minutes late on your shift, the other guys gave you the evil eye. Here, it was one of those relationships where we’d hired Mike to help us, and he was very good to work with – spending more time at the helm than anybody. We each got our sleep, but we stood watch for about four hours at a time. [RF] Did Mike have any experience with a Fleming? [BK] No, none at all. In fact, we were all very new to the Fleming. Before we pushed off on this cruise, we had a total of two hours aboard the boat. We knew the chart plotter worked, we knew the autopilot worked – we basically knew everything aboard worked, but that’s it (chuckling as he said this). [RF] What did you have for a chart plotter? [BK] It’s a Simrad – pretty old, but it worked well for us. I brought my iPad along with a Navionics chart plotter on it, and then left it in the hotel, so we had to do without it. Mike also had a laptop with a full set of charts and software, so we mostly navigated off that. There’s a really old GPS built into the boat, and we didn’t even turn it on, because we all had GPS in one form or another. I had a GPS on my iPhone, and it was working too. [AK] Yeah, 20 miles offshore our iPhones worked. I took some phone calls, and they dropped every once in a while, but we had cell coverage most of the way. [BK] The cell towers are pretty high on the coastal bluffs and hills, and they gave us pretty good coverage. We could have navigated with an iPhone if we had wanted to. Navigation was not a concern or an issue. Being an instrumented-rated pilot, navigation is one of my strong suits, so I wasn’t worried about this. [RF] Can you see lights on the shore at 20 miles out? And what was the weather like? [BK] No, we couldn’t see lights when we were that far out. As we approached Cape Flattery and we swung closer to land, we could see lights, but it was at midnight, so there weren’t many. At our furthest point out, you could vaguely make out the mountains on the coast. We had a little bit of rain, off and on, overcast skies, and I don’t remember seeing any stars the whole trip. It was pretty cold, so we didn’t spend much time out on the deck. When it started getting dark, I turned in for some sleep, and around 10PM I took over from Mike. After he got some rest, it was midnight and we were both at the helm to round Cape Flattery. At the Cape, you can take a shortcut through some rocks that are about 50 yards off the tip of the Cape, but it was dark and we decided to play it safe and swung wide around them. There was no moon, so it was pitch black dark. Once we got around the Cape and into the Strait of Juan de Fuca, we hugged the south shore and the water calmed down considerably. The Strait has great big following seas – nice, smooth, large waves, and they were very rhythmic. Our autopilot didn’t always hold course, so we had a fairly rhythmic sway. [RF] Before we talk about the Strait of Juan de Fuca, let me come back to one last question about the cruise up the Coast. Did you have any concerns about hitting floating tsunami debris from the Japan earthquake? As you might recall, a 66’ long concrete dock from Japan washed ashore on the Oregon coast about a year ago, and tons of floating debris, including half-submerged fishing boats, are washing up on Washington beaches every day. [BK] Yes, but we had little choice and never hit anything – at least, that we know of. On the radar, we could see buoys, but if there was a log ahead of us, or tsunami debris, I doubt we could see it. But we did slow down to about 8 kts once it got dark. We calculated our speed and distance to arrive at sunrise, as we didn’t want to be coming in at dark.  The Strait of Juan de Fuca is a broad expanse of water leading from the Pacific Ocean eastward to the Strait of Georgia (and Vancouver, B.C.) to the north and Washington State's Puget Sound to the south. It is a major shipping lane, with dozens of huge freighters, cargo ships, ferries, and U.S. Navy Trident submarines passing through it every day.

The Strait of Juan de Fuca is a broad expanse of water leading from the Pacific Ocean eastward to the Strait of Georgia (and Vancouver, B.C.) to the north and Washington State's Puget Sound to the south. It is a major shipping lane, with dozens of huge freighters, cargo ships, ferries, and U.S. Navy Trident submarines passing through it every day.[RF] So, tell me about your passage in the Strait of Juan de Fuca (The Strait of Juan de Fuca is a 12-mile wide expanse that separates the Olympic Peninsula of Washington State from the southern tip of Vancouver Island, leading to the San Juan Islands, Puget Sound, and Seattle to the south, and Vancouver to the northeast. This is a major shipping lane for all ocean freighter traffic, including oil tankers bound for Anacortes from the Alaskan oil fields, container ships from SE Asia bound for Vancouver, Seattle, and Tacoma, not to mention huge Trident Submarines headed to and from the U.S. Navy sub base at Bangor, WA that are traveling on the surface at this point and flanked by huge gunboats for protection. It’s a busy, busy stretch of water, and most of this traffic is traveling at 20 kts or better.) [BK] The most exciting thing that occurred was about 3AM I was at the helm and heading east into the Strait. Mike was down in his cabin catching some sleep, and I had two freighters come awfully close to me. They passed my stern, and were overtaking me. The radar is really all we had other than their running lights, which can only confirm their radar position because it is impossible to accurately judge their distance or speed from their lights. They got as close as a half a mile, although their running lights looked a lot closer. I had right-of-way, and was just trying to hold course, letting them maneuver around me. Neither ever tried hailing us on the radio nor did I feel the need to contact them. The whole process was fairly comfortable for me because of my instrument flight training and spending time flying aircraft in the clouds and having only your instruments to rely on. [RF] Do you think they saw you? [BK] Oh, yeah, they saw us! Both turned to the right just when they needed to turn to miss us and pass behind. But having two of them on my tail, almost at the same time, was rather startling – it got kind of crowded there for a few minutes. It’s like you’re definitely flying by instruments, because you can’t see anything, and you obviously know where you are in the shipping lane and you’re holding a heading. [RF] As you moved down the Strait, were you able to pick up any information from the U.S. or Canadian Vessel Traffic VHF radio channels? On the Canadian side, it’s identified as Tofino Traffic or Victoria Traffic – they give vessel traffic for the freighters coming in and out of the Strait. [BK] No, I just listened to Channel 16. There were two emergencies that lasted throughout the night and helped keep us awake – a fire on a fishing boat, and another call that reported a sunk vessel. They gave the location, but we were too far away to respond. [RF] With respect to traveling into Victoria Harbor and maneuvering around the tricky channel buoys that mark the busy floatplane lanes, you mentioned earlier that you’d already made that mistake before, and knew what to expect this time. Can you tell us about that? [BK] Well, they aren’t tricky once you know what you’re doing. Several years ago on a visit to Victoria on a charter out of Anacortes, I got waved out of a floatplane taxiway. It was really busy in there, and of course I hadn’t been in there before. I was just trying to keep separation between me and some of the other boats, so I found myself in the taxiway without realizing it. A harbor patrol boat came out and waved me away. This time through, we were able to avoid that mistake. We docked at 7AM, spent the whole of that day enjoying the city, and then departed at 7AM the next morning for Friday Harbor to clear U.S. Customs. At Victoria Marina, this was my second docking. It was a stern-in docking, and I had to back down with a bit of crosswind, and I wanted to get some experience with that. Mystic Dancer doesn’t have a stern helm station, so this was all done from the pilot house. It went well, as did my eventual back-in docking at our slip at Anacortes. It was good practice. Actually, my first-ever docking with Mystic Dancer was at Astoria on the first evening out – and at midnight, in pitch black darkness. We were so close to the entrance of that harbor – within 50’ of it – and couldn’t see it. The entrance is an S-turn made from a wall of pilings coated with creosote, which you can’t see at all at night, and you completely lose depth perception [RF] Anne, you indicated you worked the Customs clearance. Given this was a brand new boat to you, and after leaving Portland (obviously in the U.S.), you stopping off in Victoria (obviously in Canada) – was there anything interesting that U.S. Customs wanted to ask you about? [AK} You know, it was pretty simple. Once I docked the boat, there’s a phone on the dock, and they basically wanted to know if we had our paperwork. A single Customs agent came down, asked a few questions about food – and so I had to give up my berries and some veggies. He didn’t really board – he came into the pilot house to look at Bill’s cigars to make sure they weren’t Cuban, but he had no interest in coming down to the galley to look through the fridge to make sure I was giving up all I had. Knowing we had just taken delivery of this boat, he asked a few questions about that and we explained the situation. He was wondering why we went to Victoria, and we said it's just such a pretty city – it was on the way, so why not stop. [BK] Looking back on it, I realize this was a pretty aggressive cruise, but we were relying heavily on Captain Cregan. [RF] So, what are your future plans for cruising? [AK] Well, first it’s to explore the San Juan Islands more, then the Inside Passage, and our dream is to do a longer, more extensive cruise to SE Alaska. [BK] And I’d like to return to the west side of Vancouver Island. There are three really neat bays there, starting with Barkley Sound on the southwestern end. On the east side of Vancouver Island, we’ve also been into Princess Louisa Inlet north of Vancouver, and we’d like to return there. [RF] Anne, are you going to be active in running the boat? [AK] I did the Victoria to Friday Harbor to Anacortes legs, and I docked the boat at the Cap Sante fuel dock in Anacortes. I’ve also taken a week-long sailing course, so I’m well acquainted with chart reading, navigation, and boat handling. [RF] Thanks Bill and Anne, welcome to the Fleming Owner’s Forum, and I wish you many happy years of cruising on Mystic Dancer. |

||||

| Copyright © 2010 MDT Consulting. All rights reserved. | Visit the Fleming manufacturer's web site | Use & Privacy Policy | Contact us |