|

|

|

|||

|

|

|||||

| Inside Passage Wildlife - White, Grizzly, and Black Bears | ||||

|

By Ron Ferguson, written September 22, 2011

There's nothing mundane about cruising the famed Inside Passage from Seattle to SE Alaska. The scenic beauty matches anything you'll ever see anywhere in the world, and the wildlife is just amazing. It's hard to imagine ever being bored in these cruising grounds. Will I See Bears All Along The Inside Passage? When we first began cruising the Inside Passage, I thought we’d see bears almost every day, milling around on the shorelines just waiting to pluck spawning salmon from the icy waters, or whatever. Oddly enough, it just didn’t happen. It’s safe to say that the total number of bears we’ve seen in five years of cruising these incredible waters can be counted on one hand. Usually, but not always, the only reason you’ll see a bear on the shore is because he or she is there to get food. They certainly aren’t there for the salt water – it’s as undrinkable for them as it is for us. They won’t be there for salmon unless you’re at the outflow of a spawning stream, and there just aren’t very many of those as you cruise along. If the bear was looking for berries, or a tree trunk to scratch his back, he’d do that in the forest, and not at the shoreline. The truth is, you’re going to find bears at fairly well known places – places where they’ve been observed to come on a frequent basis. There are a half dozen of those along the Inside Passage, and because everyone goes there, we don’t. On the other hand, the occasional bear that we’ve seen has been very interesting, and they make for pretty good story. The Spirit Bear In 2008, my wife, Kap, and I went the full route of the Inside Passage, departing from Anacortes, Washington, in late May, dawdled our way through the incredibly scenic passages in Canada’s British Columbia, and arrived in Ketchikan, AK, in mid-June. We continued north to Juneau, then west to Glacier Bay National Park, then further west to visit Sitka, and finally returned in early September. On our journey north, and a few days after our arrival in Ketchikan – the first stop for all cruisers heading north, as it’s a Customs port of call from Canada to the U.S. – we took an unusual route, circumnavigating Revillagigedo Island, the large island that Ketchikan is on. East of Revillagigedo Island (the locals just call it “Revy”) is Misty Fjord and we’d heard it was well worth the visit. Many of the cruisers on the Inside Passage bypass it because it’s a bit out of the way, and doesn’t have the cachet of the more famous Glacier Bay National Park further north. We were in no hurry, so we decided to spend a week going around Revy. After a few days in Misty Fjord, we continued north, and early one morning as we came around the top end of the island, we were on the watch (as always) for any sign of a bear along the water’s edge. Standing in the pilot house, I put the binoculars to a grassy area on the south shore of Bell Island, and what did I see – a Spirit Bear! No . . . it’s just a white rock, fooling me like so many other rocks along the shore. But wait a minute – rocks don’t move, and I’m sure I just saw that white one move! I put the long eyes to it again, and sure enough, it was a bear - and a white bear at that! In this part of the world, if it’s a white bear, it has to be a Spirit Bear!

This is the shoreline along Bell Island where I first spotted a “white rock” at the water’s edge that seemed to move – that’s what caught my eye. I put the binoculars to it, and sure enough, it was a Spirit Bear. Unfortunately, this photo is the closest we were able to get to him before our engine noise spooked him and he ran into the woods for safety. In the photo, he’s at the center, right at the water’s edge. (You'll probably have to click on the image to see him.)

This is the shoreline along Bell Island where I first spotted a “white rock” at the water’s edge that seemed to move – that’s what caught my eye. I put the binoculars to it, and sure enough, it was a Spirit Bear. Unfortunately, this photo is the closest we were able to get to him before our engine noise spooked him and he ran into the woods for safety. In the photo, he’s at the center, right at the water’s edge. (You'll probably have to click on the image to see him.) Here’s what “our” Spirit Bear looks like from the next photo I took – this is the best I can digitally zoom in.

Here’s what “our” Spirit Bear looks like from the next photo I took – this is the best I can digitally zoom in.I grabbed the only camera we had on board – a small point-and-shoot Canon SureShot digital camera, with a puny zoom lens. I snapped about a dozen photos, but we were almost a quarter mile away and I was sure none would turn out. I urged Kap to move closer to the shore – but slowly and quietly so that we wouldn’t spook this guy. Unfortunately, our engine noise, even at idle speed, made him nervous and he immediately moved behind some rocks for cover, then made his way across the shore and back into the trees. Damn! The one time in my life that I’ll probably ever see a Spirit Bear, and all I have is a ridiculous point-and-shoot camera. I vowed that as soon as we got to Juneau, I’d get the best camera in town. That turned out to be a Nikon D60, with two extra long lens, and it was one of the best things I’ve bought for our cruising.  This photo was taken from the National Geographic web site (http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2011/08/kermode-bear/barcott-text) of a Kermode Bear (aka Spirit Bear) in a moss-draped rain forest in British Columbia. See for yourself if he looks exactly like the one we saw north of Ketchikan. (The article on that National Geographic web page is very interesting.)

This photo was taken from the National Geographic web site (http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2011/08/kermode-bear/barcott-text) of a Kermode Bear (aka Spirit Bear) in a moss-draped rain forest in British Columbia. See for yourself if he looks exactly like the one we saw north of Ketchikan. (The article on that National Geographic web page is very interesting.)Officially, the Spirit Bear is known as the Kermode bear; sometimes as the "ghost bear". And it’s not an albino, nor is it related to polar bears. And don't confuse it with a brown bear, which is known as the grizzly bear. Rather, the Spirit Bear is a genetically unique subspecies of the North American black bear, arising from a recessive gene that gives them a white or cream-colored coat. As National Geographic says, they’re “a walking contradiction – a white black bear”. Because of their ghost-like appearance, the Spirit Bear holds a prominent place in the Aboriginal mythology of the area. It’s not unusual for Spirit Bears to have a bit of cream color somewhere in their coat. This little guy we saw was cream colored at the shoulder and head, but almost pure white from there back to his tail. He (and I’m not making any suggestions about his sex) was incredibly muscular, with a very large shoulder, and boy, could he move when spooked by us, even though we hadn’t made any moves that would have seemed threatening.  This Google Map image shows the area that the Inside Passage covers on the 950 mile trek from Seattle to Juneau. At this scale, much of the actual Inside Passage route is on waterways that are too small to even be seen. The only unprotected water (i.e., exposed to the often massive Pacific Ocean swells) is Queen Charlotte Sound at the northern tip of Vancouver Island, and Dixon Entrance, a stretch of open water between Prince Rupert, B.C. and the Alaska border.

This Google Map image shows the area that the Inside Passage covers on the 950 mile trek from Seattle to Juneau. At this scale, much of the actual Inside Passage route is on waterways that are too small to even be seen. The only unprotected water (i.e., exposed to the often massive Pacific Ocean swells) is Queen Charlotte Sound at the northern tip of Vancouver Island, and Dixon Entrance, a stretch of open water between Prince Rupert, B.C. and the Alaska border.

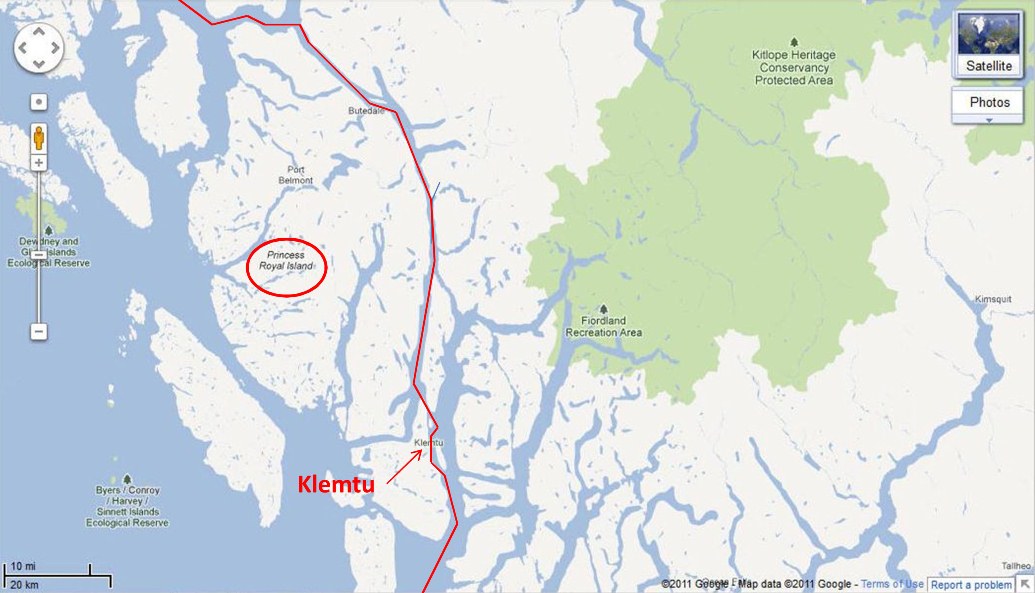

Visiting Klemtu To get some perspective on our sighting of the Spirit Bear, let’s back up a bit. A week earlier we spent an overnight at the tiny First Nations village of Klemtu. We had just finished a relatively short 36 nautical mile run from Shearwater, B.C. that day, first traveling NW up Seaforth Channel, across Milbanke Sound, and then NE into Finlayson Channel – a long narrow channel that leads into the deepest inland part of the Inside Passage. Klemtu is on the east side of Swindle Island, tucked into an even narrower channel behind Cone Island (may of the place names here are very descriptive – Cone Island is a perfectly conical cone that rises out of the water, and you just know it has volcanic origins).  This small section of the Inside Passage just shows Finlayson Channel – maybe 75 miles of the entire 950 mile natural waterway. I had to use the Map view rather than Satellite, as the entire area was covered in snow when the satellite images were taken and it shows very little. Most of this channel is ½ mile wide at most.

This small section of the Inside Passage just shows Finlayson Channel – maybe 75 miles of the entire 950 mile natural waterway. I had to use the Map view rather than Satellite, as the entire area was covered in snow when the satellite images were taken and it shows very little. Most of this channel is ½ mile wide at most. This is the first glimpse you get of Klemtu as you round the tip of the peninsula protecting the tiny harbor of Klemtu.

This is the first glimpse you get of Klemtu as you round the tip of the peninsula protecting the tiny harbor of Klemtu. The Klemtu long house, built in 2000 for the local First Nations community. The wood used was all locally sourced, and an expert long house craftsman from the First Nations village of Alert Bay (near Port McNeill, about 100 miles south) came up to supervise the construction.

The Klemtu long house, built in 2000 for the local First Nations community. The wood used was all locally sourced, and an expert long house craftsman from the First Nations village of Alert Bay (near Port McNeill, about 100 miles south) came up to supervise the construction.The first building you see as you round the tip of a peninsula leading into Klemtu’s small harbor is a First Nations long house – looking fairly new and with tribal images painted on the exterior. We tied up at Klemtu’s government dock – but getting into it was touch and go. The tiny dock was only large enough for four cruiser-sized boats, two on each side of the dock. Our bow was within 5’ of the shore, and luckily, the water depth dropped very steeply. We were at high tide on arrival, and although a couple of guys on the dock told us it was “plenty deep”, our concern was, what will it be later this afternoon at low tide? (Tidal change here can be as much as 20’.) Klemtu has a population of 160 (or so), and a very quick stroll around the town convinced us there wasn’t much here. At the government dock there’s a fairly new fish processing factory and a sign on the building’s wall indicates it is “Proudly a fish farm facility” – which means they use farmed Atlantic salmon that are almost universally unpopular around these parts (and in fact, the next day we toured a Pacific salmon fish hatchery further north at Hartley Bay, and the First Nations manager of it railed at the use of farmed Atlantic salmon and the ecological damage it’s doing). Next door to the fish processing plant was a very run down café, but quite busy with locals. After confirming with them that moorage fees were not necessary at the government dock, we asked about a possible tour of the long house. The lady behind the counter said, “Oh, that’s Francis who does that – I’ll call him for you”. She did, and we were told to head right over and he would meet us there.  Francis was our guide to the First Nations long house at Klemtu. We’re not exactly sure what Francis’ role is in this tiny village, but he seems to be in charge of the long house – and is rightfully proud of it.

Francis was our guide to the First Nations long house at Klemtu. We’re not exactly sure what Francis’ role is in this tiny village, but he seems to be in charge of the long house – and is rightfully proud of it. Kap tried her hand at the log drum behind the curtain of the ceremonial dance area – it really works!

Kap tried her hand at the log drum behind the curtain of the ceremonial dance area – it really works!Sure enough, Francis arrived shortly after we did. He was a character –very gentle, obviously First Nations, shy at first, but the more he spoke, the more animated and open he became. Over the course of the next two hours, he gave us a very extensive tour of the community’s wonderful long house, completed in 2000 and used quite extensively for community gatherings. He told us the people of Klemtu were drifting apart, and after the long house was built, it had a profound effect in bringing the people together again. (Interestingly, everyone we met on the streets in town was quite friendly, and most were young people – but to a person, every one of them had an iPod speaker stuck in their ear. We wondered what the long term prognosis was for the culture within that generation.) At the end of our tour, Francis (never did catch his surname) spoke at length about the Spirit Bear – and it was hard to tell what was true and what was myth. According to Francis, we should carefully watch the shoreline on Princess Royal Island for Spirit Bears, and he felt certain we’d see one. We’d be cruising along Princess Royal Island for most of the next day, so this was exciting news. Francis then went on to say that he regularly visits Princess Royal Island, and quite often he’ll be sitting on a log or on a rock on the beach pondering some really weighty issue that affects his people, and a Spirit Bear will quietly come up to his side, sit with him while he thinks, and soon he’ll have the answer to his thoughts. According to Tsimshian First Nations legend, the Spirit Bear has great powers, and obviously Francis felt one of these great powers helped him with answers to his imponderable questions. Legend also has it that Raven, the Creator, created every tenth black bear of Princess Royal Island as a white Spirit Bear, as a reminder of the time when the land was covered with ice and snow (the Ice Age). Lastly, Francis scoffed at the notion that the Spirit Bear is rare – although every study I’ve seen indicates there are less than 400 White Bears – yet Francis said they are very common on Princess Royal Island – but that only the First Nations people could see most of them. Spirit Bear Territory An interesting facet of our Spirit Bear sighting a week after this discussion in Klemtu is that, by all accounts, he isn’t supposed to be where we spotted him. According to the web site, www.bearsoftheworld.net/kermode_bears, “Kermode bears can only be found in what is known as the Great Bear Rain Forest located in west-central British Columbia and a few adjacent islands. They are so rare that even people who live in the region rarely see them. The highest concentration of Kermode bears can be found on and around Princess Royal Island.” From Jane Goodall’s Planet Releaf site (www.janegoodall.ca/planet-releaf/SpiritBear), “Today, there are less than 200 spirit bears left in the world, living solely in coastal British Columbia. It is unknown why Kermode bears only exist on the few islands on the coast of B.C., but in order to someday unlock this mystery we must sustain the delicate ecological balance that produces the white bear.” And not to labor a point, the Vahlhalla Wilderness Society (www.vws.org/project/spiritbear/about_bear/faq) states to the question: “Where do spirit bears live? Answer: The spirit bear inhabits only one place on Earth: the central and north coast of British Columbia, Canada from about Rivers Inlet to Stewart.” When I tracked down where this lies on a map, I found that Rivers Inlet is at the top of the Queen Charlotte Sound, just north of the top end of Vancouver Island, and Stewart in just inside the Canada/U.S. border – and about 50 miles due east of where we spotted our friend on Bell Island – so this one has it close to correct. Maybe Canada wants to believe that only they have Spirit Bears, but in fact, Bell Island is in SE Alaska, and it lies about 250 miles north of the northern tip of Princess Royal Island. It would seem the habitat for Spirit Bears isn’t as constricted as some people think. Grizzly Sighting In Glacier Bay National Park But wait! There’s more! Another interesting bear sighting occurred a couple of weeks later while cruising around in Glacier Bay National Park.  The scenic beauty of Glacier Bay National Park is beyond belief. This photo was taken at sunset while at anchor in a bay outside Gustavus, the small town at the entrance to the Park.

The scenic beauty of Glacier Bay National Park is beyond belief. This photo was taken at sunset while at anchor in a bay outside Gustavus, the small town at the entrance to the Park.Glacier Bay has to be the single most popular destination of all cruisers heading north on the Inside Passage. That’s also true for the 6 huge cruise ships that carry tens of thousands of passengers, hoping for that unique SE Alaska experience that no one else is enjoying.  Glacier Bay is called that for good reason – there are lots of glaciers within this large bay of bays. This is a fairly close photo of John Hopkins Glacier, at the head of John Hopkins Inlet. This is considered a tidewater glacier – meaning that it “flows” right up to the water’s edge and calves into the water. Supposedly, this is the only glacier in the Park that is currently advancing from the east side of the Fairweather Range of mountains – the rest are all receding at a fairly rapid rate. The glacier flows down the valley at about 3,000’/year, or about 8’/day.

Glacier Bay is called that for good reason – there are lots of glaciers within this large bay of bays. This is a fairly close photo of John Hopkins Glacier, at the head of John Hopkins Inlet. This is considered a tidewater glacier – meaning that it “flows” right up to the water’s edge and calves into the water. Supposedly, this is the only glacier in the Park that is currently advancing from the east side of the Fairweather Range of mountains – the rest are all receding at a fairly rapid rate. The glacier flows down the valley at about 3,000’/year, or about 8’/day.Nevertheless, this magnificent national park is definitely all it’s cracked up to be, and we had a great time. Because of the environmental sensitivity of the area, plus the large numbers of boat that would otherwise be here, entrance permits are strictly controlled. With the help of friends who knew the ins and outs of how to get an application accepted, we obtained a one-week permit.  The waters are full of “bergie bits” – pieces of icebergs that have calved off from tidewater glaciers. This one looked small enough to bring aboard – the ice is absolutely crystal clear, and resists melting in a cocktail at least 5 times longer than regular – the result of the immense pressure squeezing out every last air bubble.

The waters are full of “bergie bits” – pieces of icebergs that have calved off from tidewater glaciers. This one looked small enough to bring aboard – the ice is absolutely crystal clear, and resists melting in a cocktail at least 5 times longer than regular – the result of the immense pressure squeezing out every last air bubble. Here’s what that same iceberg looked like when we got him up onto the swim step – all 150 pounds of him. He lasted in our ice chest for the remainder of the cruise, and we still have a bit of him in our freezer at home as a souvenir.

Here’s what that same iceberg looked like when we got him up onto the swim step – all 150 pounds of him. He lasted in our ice chest for the remainder of the cruise, and we still have a bit of him in our freezer at home as a souvenir. Some of the cruisers dare to get right up to the face of the glaciers that extend down to the water’s edge. We were much more cautious. Several of the glaciers had recently calved, and the water out in the main channels was full of bergie bits, and even if the portion above water looks small, keep in mind that 90% of a bergie bit is underwater. As the one in this photo illustrates, they can also be almost invisible, and we felt a bow watch was mandatory (that round-ish blob in the photo center is an almost clear bergie bit, with very little above the surface – if any at all – and it would be a disaster to hit).

Some of the cruisers dare to get right up to the face of the glaciers that extend down to the water’s edge. We were much more cautious. Several of the glaciers had recently calved, and the water out in the main channels was full of bergie bits, and even if the portion above water looks small, keep in mind that 90% of a bergie bit is underwater. As the one in this photo illustrates, they can also be almost invisible, and we felt a bow watch was mandatory (that round-ish blob in the photo center is an almost clear bergie bit, with very little above the surface – if any at all – and it would be a disaster to hit). Most people arrive in Glacier Bay National Park by large cruise ship – with 3,000 of their closest friends aboard – but we arrived on our own private cruise ship.

Most people arrive in Glacier Bay National Park by large cruise ship – with 3,000 of their closest friends aboard – but we arrived on our own private cruise ship.But back to bears. The next day we were cruising in Geibie Inlet looking for a place to anchor for the night. As we cruised along we spotted another one of those slightly “moving rocks” on the shore.  Here’s what a “moving rock” looks like to the naked eye – almost nothing perceptible. Even clicking on the photo to enlarge it a bit won't help to see it

Here’s what a “moving rock” looks like to the naked eye – almost nothing perceptible. Even clicking on the photo to enlarge it a bit won't help to see it

But when you later crop it, you can now make out the butt end of a very big brown bear – or more commonly known as a grizzly bear. We followed this guy for at least a half hour as he slowly ambled down the rocky beach, turning over a rock now and again, but basically just out for a stroll.

But when you later crop it, you can now make out the butt end of a very big brown bear – or more commonly known as a grizzly bear. We followed this guy for at least a half hour as he slowly ambled down the rocky beach, turning over a rock now and again, but basically just out for a stroll. Here’s a better shot of him, cropped from a photo taken a bit further down the beach to bring him in closer. You can make out the dark fur along the hump at his shoulder (which is a trait of grizzlies), and he looks like a very, very muscular grizzly bear – the kind you wouldn’t want to meet in the woods.

Here’s a better shot of him, cropped from a photo taken a bit further down the beach to bring him in closer. You can make out the dark fur along the hump at his shoulder (which is a trait of grizzlies), and he looks like a very, very muscular grizzly bear – the kind you wouldn’t want to meet in the woods.He ambled along like he didn’t have a care in the world – and I’m sure he wasn’t worried by partisan politics, or the global financial crisis, or whether he could make his house payment – no, he just strolled along for the longest time while we snapped dozens of photographs. Unfortunately, he didn’t have anyone to cavort with on the rocky beach. He didn’t play Kick The Can, or play any beach volleyball for us – you know, all the stuff that everyone else claims they saw (somebody else’s story is always better, you know). Suddenly, my camera flashed a message to change the battery and I couldn’t take any more photos until I scrambled to locate and load my backup battery. Just then, Kap hollered, “Get a photo, he’s scratching his back on the rock! Quick! Quick!” I looked up to see this seemingly gentle giant raise to his full height, face towards us, and scratched his back for the longest time on the sharp ridges of a rock. The rock was at least 8’ tall, and his head was just about even with the top of the rock. Alas, by the time I got my camera battery loaded his back was scratched sufficiently well, and he resumed his amble.  By the time I got my camera battery re-loaded, our grizzly had finished his back scratching on the large moss-covered rock and moved on. He had raised himself to the full height of the large rock that you see behind him, standing on his hind legs with his face towards us, and used the vertical ridge in the center of the rock as his back scratcher. Man, was this guy big!

By the time I got my camera battery re-loaded, our grizzly had finished his back scratching on the large moss-covered rock and moved on. He had raised himself to the full height of the large rock that you see behind him, standing on his hind legs with his face towards us, and used the vertical ridge in the center of the rock as his back scratcher. Man, was this guy big! For the next fifteen minutes, we just idled along as quietly as we could, watching this incredibly powerful mammal stroll along the beach. Every once in a while he’d jog to his right to search out something in the tall grass, but would then return to the rocky beach area.

For the next fifteen minutes, we just idled along as quietly as we could, watching this incredibly powerful mammal stroll along the beach. Every once in a while he’d jog to his right to search out something in the tall grass, but would then return to the rocky beach area.Finally, he reached a dry stream bed – one that he might have known in the past carried spawning salmon – and after searching around there for about 10 minutes he slowly made his way back into the dense forest. Our bear encounter was over. Bear Watching Made Easy Many of the cruisers to SE Alaska plan a side trip to the Anan Creek Bear Observatory, about halfway between Ketchikan and Wrangell. You can fly there from Ketchikan, or take a boat from Wrangell – or better yet, stop by on your own boat and tie up at the guest dock close to the observatory. I took the following photos from the U.S. Forest Service web site, at: www.fs.fed.us/r10/tongass/recreation/wildlife_viewing/anan_album.  The U.S. Forest Service has built a viewing platform, screened-in for protection, that lets humans get within just a few feet of bears feeding on spawning salmon that are passing through.

The U.S. Forest Service has built a viewing platform, screened-in for protection, that lets humans get within just a few feet of bears feeding on spawning salmon that are passing through.There’s a boardwalk on one side of a spawning stream, and the bears congregate on the other side – just a handful of feet away from you – and at times there are as many as 20 bears gorging on salmon that they snag by hand as they come through. Both brown (grizzly) and black bears feed here, but usually don’t mix at the same time here. Access to the Anan Creek site is very restricted by the U.S. Forest Service, and only 60 visitors a day are allowed in. On our next cruise to SE Alaska we’ll probably make time to stop by Anan Creek. It’s actually the best chance to safely get up close and watch these amazing creatures do what they do best – fish. |

||||

| Copyright © 2010 MDT Consulting. All rights reserved. | Visit the Fleming manufacturer's web site | Use & Privacy Policy | Contact us |